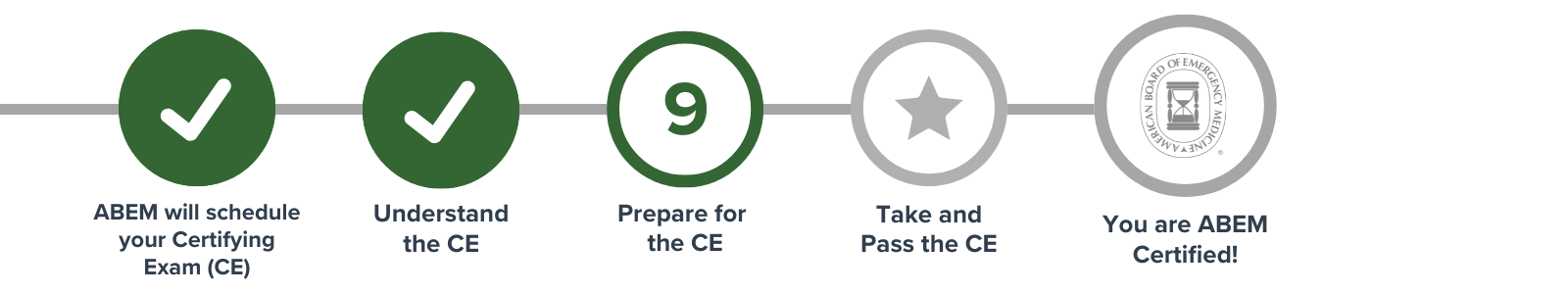

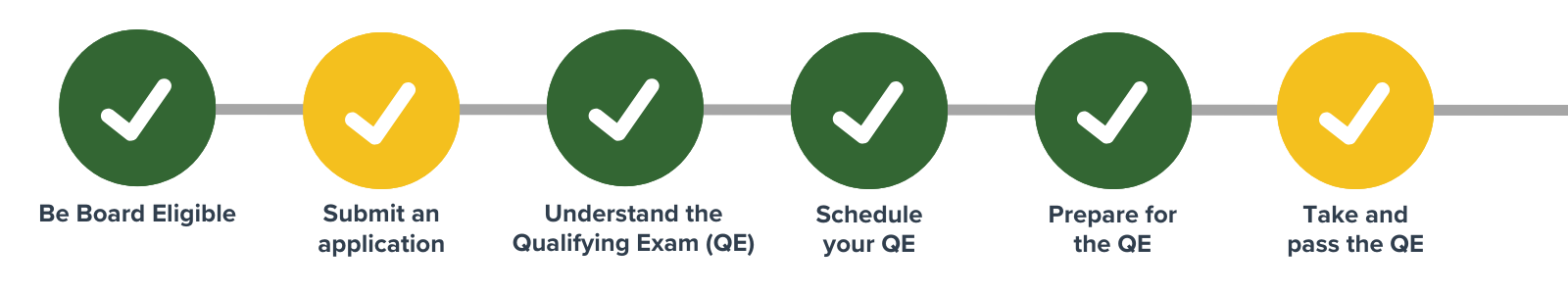

- Get Certified

- Certification Process

- Subspecialties and FPDs

- Focused Practice Designations

- Anesthesiology Critical Care Medicine

- Emergency Medical Services (EMS)

- Health Care Administration, Leadership, & Management (HALM)

- Hospice and Palliative Medicine

- Internal Medicine – Critical Care Medicine

- Medical Toxicology

- Neurocritical Care

- Pain Medicine

- Pediatric Emergency Medicine

- Sports Medicine

- Undersea and Hyperbaric Medicine

Certifying Exam Content

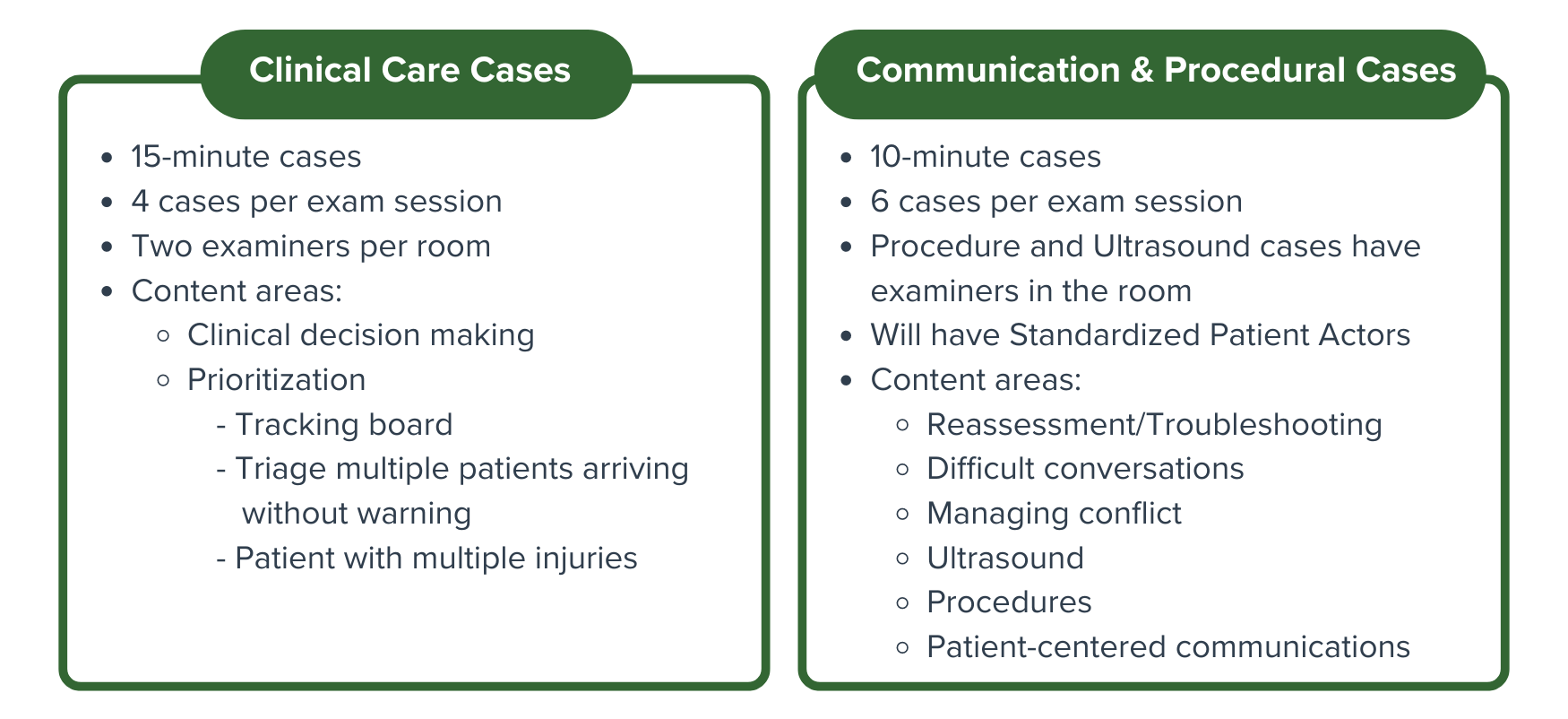

Case Types

The Certifying Exam will allow candidates to use the skills and methods learned in training and apply them to simulated, real-world clinical scenarios to determine if they meet the high standards required for the independent practice of Emergency Medicine. Learn how cases are developed

There are two assessment types that make up the new Certifying Exam: Clinical Care Cases and Communication & Procedure Cases.

Case Summaries & Sample Case Videos

Each case will assess different competencies important to the specialty. Below are resources highlighting the overall knowledge, skills, and abilities of a successful candidate for each case.

Quicklinks:

Certifying Exam Case Summaries

Clinical Decision-Making

Emergency physicians see patients with undifferentiated presentations. Clinical Decision-Making (CDM) cases are structured discussions designed to assess a candidate’s ability to evaluate and treat such patients. A successful candidate will be able to explain their thought processes behind certain decisions made during the various phases of a clinical encounter.

Difficult Conversations

Having difficult conversations such as breaking bad news to patients and families is an essential skill for an emergency physician. These discussions may include sensitive, unwanted, or unexpected information. A successful candidate will establish rapport and effectively communicate in an empathetic manner.

Managing Conflict

Managing conflict (e.g., negotiating) is an essential skill for an emergency physician. This case requires the physician to navigate a differing position to negotiate a mutual understanding for a patient-centered outcome. A successful candidate will create solutions to the situations in which they are involved.

Patient-Centered Communications

Engaging and being able to effectively communicate with patients and families are essential skills for an emergency physician. The Patient-Centered Communication (PCC) cases focus on both the content and the process of communication with a patient. A successful candidate will empathically use verbal and nonverbal skills to engage in bidirectional communication that is essential for a successful therapeutic encounter in the emergency department.

Prioritization

A hallmark of emergency medicine is the ability to triage or prioritize care. This case will require the physician to evaluate and treat multiple patients while ensuring those who require immediate care receive it quickly. The physician may face the arrival of additional patients, the deterioration of existing patients, and realistic workflow interruptions during the case. A successful candidate will identify and stabilize high acuity patients.

Procedures

Emergency physicians must regularly perform procedures in the emergency department. The procedural case evaluates a candidate’s ability to perform skills that are integral to the practice of emergency medicine. A successful candidate will demonstrate the preparation for the procedure (i.e. indications, risks), the performance of the procedure, and the provision of post-procedure care.

Download the Procedures List

(NEW – April 2025)

Ultrasound

Point-of-care ultrasound is an essential skill that is integrated into clinical practice. The candidate must be able to explain the ultrasound study to a standardized patient. Based on the clinical scenario that is presented, the candidate will efficiently acquire quality views while an examiner operates the ultrasound machine (i.e., knob adjustment). A successful candidate will be able to describe relevant anatomy and interpret pathologic images.

Download the Ultrasound List

(NEW – May 2025)

Reassessment

Emergency physicians frequently address incomplete, changing, or conflicting information. These cases will present the candidate with clinical data or circumstances that require a reassessment of a patient’s condition. The successful candidate will demonstrate the ability to evaluate new information, efficiently problem solve, and optimize patient management.

Case References

References are provided as an example of content used to develop cases. This list does not represent the totality of material for each topic. The everyday practice of Emergency Medicine is the lens through which these resources should be viewed.

Case Development References

Clinical Decision-Making:

- Beeson MS, Bhat R, Broder JS, et al. The 2022 Model of the Clinical Practice of Emergency Medicine. J Emerg Med. 2023;64(6):659-95. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2023.02.016. PMID: 32475725

- American Board of Emergency Medicine. 2021 KSAs. Updated December 7, 2020. Accessed June 25, 2024.

Difficult Conversations:

- Baile WF, Buckman R, Lenzi R, Glober G, Beale EA, Kudelka AP. SPIKES-A six-step protocol for delivering bad news: application to the patient with cancer. Oncologist. 2000;5(4):302-11. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.5-4-302. PMID: 10964998

- Hobgood C, Harward D, Newton K, Davis W. The educational intervention “GRIEV_ING” improves the death notification skills of residents. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12(4):296-301. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2004.12.008. PMID: 15805319

- Lilley EJ. Navigating Difficult Conversations: Breaking Bad News and Exploring Goals of Care in Surgical Patients. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2021;30(3):535-543. doi:10.1016/j.soc.2021.02.010. PMID: 34053667

- Makoul G. Essential elements of communication in medical encounters: the Kalamazoo consensus statement. Acad Med. 2001;76(4):390-3. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200104000-00021. PMID: 11299158

- Wall, et al. End of Life-Death in the ED. In: Rosen’s Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice (10th Edition). New York: Elsevier; 2023:2450-2451.

- Tintinalli, et al. Death Notification and Advance Directives. In: Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide (Ninth Edition). New York: McGraw-Hill; 2020:2017-2020.

Managing Conflict:

- Back AL, Arnold RM. Dealing with conflict in caring for the seriously ill: “it was just out of the question”. JAMA. 2005;293(11):1374-81. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.11.1374. PMID: 15769971

- Garmel, GM. Conflict resolution in Emergency Medicine. In: Adams, JG, editor. Emergency Medicine: Clinical essentials. (2nd Ed.) Philadelphia: Saunders/Elsevier, 2013:2171-2185

- Fisher R, Ury W, Patton B. Getting to Yes. LearnCom; 2006.

- Tjan TE, Wong LY, Rixon A. Conflict in emergency medicine: A systematic review. Acad Emerg Med. 2024;31(6):538-546. doi: 10.1111/acem.14874.

- Ripley A. HIGH CONFLICT: Why We Get Trapped and How We Get Out. Simon & Schuster; 2022.

Patient-Centered Communications:

- Fortin AH, Smith RC. Smith’s Patient-Centered Interviewing: An Evidence-Based Method. McGraw-Hill Medical; 2012.

- Makoul G. Essential elements of communication in medical encounters: the Kalamazoo consensus statement. Acad Med. 2001;76(4):390-3. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200104000-00021. PMID: 11299158

- Makoul G. The SEGUE Framework for teaching and assessing communication skills. Patient Educ Couns. 2001;45(1):23-34. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(01)00136-7. PMID: 11602365

- Levinson W, Lesser CS, Epstein RM. Developing physician communication skills for patient-centered care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(7):1310-8. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0450. PMID: 20606179

- Skillings JL, Porcerelli JH, Markova T: Contextualizing SEGUE: Evaluating residents’ communication skills within the framework of a structured medical interview. J Grad Med Educ. 2010;2(1):102-7. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-09-00030.1.PMID: 21975894

Prioritization:

- Ratwani RM, Fong A, Puthumana JS, Hettinger AZ. Emergency physician use of cognitive strategies to manage interruptions. Ann Emerg Med. 2017;70(5):683-687. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2017.04.036 PMID: 28601266

- Skaugset LM, Farrell S, Carney M, et al. Can you multitask? Evidence and limitations of task switching and multitasking in emergency medicine. Ann Emerg Med. 2016;68(2):189-195. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2015.10.003 PMID: 26585046

- Iserson KV, Moskop JC. Triage in Medicine, Part I: Concept, History, and Types. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49(3):275-281. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.05.019 PMID: 17141139

- Moskop JC, Iserson KV. Triage in Medicine, Part II: Underlying Values and Principles. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49(3):282-287. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.07.012 PMID: 17141137

- Hendrickson RG, Horowitz B. Disaster Preparedness. In: Tintinalli JE, Ma O, Yealy DM, Meckler GD, Stapczynski J, Cline DM, Thomas SH. eds. Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide, 9e. McGraw-Hill Education; 2020.

Procedures:

- Custalow CB, Hedges JR, Roberts JR, Thomsen TW. Roberts and Hedges’ Clinical Procedures in Emergency Medicine. Elsevier/Saunders; 2014.

- Barsuk JH, McGaghie WC, Cohen ER, O’Leary KJ, Wayne DB. Simulation-based mastery learning reduces complications during central venous catheter insertion in a medical intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(10):2697-2701. PMID: 19885989

- Lammers RL, Davenport M, Korley F, et al. Teaching and Assessing Procedural Skills Using Simulation: Metrics and Methodology. Acad Emerg Med. 2008;15(11):1079-1087. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00233.x PMID: 18828833

- Beeson MS, Bhat R, Broder JS, et al. The 2022 Model of the Clinical Practice of Emergency Medicine. J Emerg Med. 2023;64(6):659-95. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2023.02.016. PMID: 32475725

Ultrasound:

- Haidar DA, Peterson WJ, Minges PG, et al. A consensus list of ultrasound competencies for graduating emergency medicine residents. AEM Educ Train 2022, 6(6), e10817. doi:10.1002/aet2.10817 PMID: 36425790

- American College of Emergency Physicians. Emergency ultrasound imaging criteria compendium. American College of Emergency Physicians. 2021

- Atkinson P, Bowra J, Lambert M, et al. International Federation for Emergency Medicine point of care ultrasound curriculum CJEM. 2015;17(2):161-70. doi: 10.1017/cem.2015.8 PMID: 26052968

- Esener D, Rose G, editors. Sonoguide [Internet]. 2nd ed. American College of Emergency Physicians; c2021. [cited 2024 Jun 20]. Available from: https://www.acep.org/sonoguide.

Reassessment/Troubleshooting:

- Cheung DS, Kelly JJ, Beach C, et al. Improving handoffs in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;55(2):171-180. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2009.07.016 PMID: 19800711

- Hern HG Jr, Gallahue FE, Burns BD, et al. Handoff Practices in Emergency Medicine: Are We Making Progress?. Acad Emerg Med. 2016;23(2):197-201. doi:10.1111/acem.12867 PMID: 26765246

- Kessler C, Shakeel F, Hern HG, et al. An algorithm for transition of care in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2013;20(6):605-610. doi:10.1111/acem.12153 PMID: 23758308

- Smith D, Burris JW, Mahmoud G, Guldner G. Residents’ self-perceived errors in transitions of care in the emergency department. J Grad Med Educ. 2011;3(1):37-40. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-10-00033.1 PMID: 22379521